by Andrew Zirschky, Ph.D.

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt of Dr. Andrew Zirschky’s book Beyond the Screen: Youth Ministry for the Connected But Alone Generation, published in 2015 by Abingdon Press.

All is not well in the brave new world of networked individualism. Teenagers are coming of age in a world that “confers social and economic advantages to those who behave effectively as networked individuals.”[1] But behaving as a networked individual—meeting the demands of this new social operating system—is not without drawbacks.

As with any social system, networked individualism demands that its inhabitants behave in certain ways in order to be socially successful. Those who lived in the era of door-to-door community had to conform to social expectations or face being shunned by the village. Those who lived in the era of place-to-place community had to attend group meetings, services and functions, or face being cut off from community. And when we consider networked individualism, we find four demands placed upon teenagers. Meeting these demands can have negative effects.[2]

Demand #1: Create a Personal Network

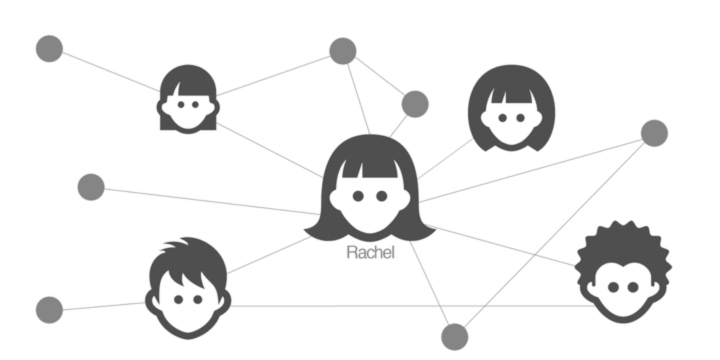

True to its name, networked individualism requires an individual to establish a unique set of personal relationships (what sociologists call an egocentric network) from which she receives care and support. This is how Rachel, a teenager from rural Tennessee, experiences community. She doesn’t find her identity and community in any one group, rather she’s at the center of a network of friends and acquaintances who are connected directly to her. Her friends from church are part of her network, but not everyone who attends youth group is part of Rachel’s network. A few girls from the lunch table are part of her network, but not all of them. In the networked world, joining a pre-existing group doesn’t guarantee meaningful community. So either youth, like Rachel, successfully build a network through their own effort, or they are likely to face some level of relational isolation. Building a network involves finding friends from across a variety of social groups and then keeping those connections open. For close connections, Rachel communicates daily or even more often whether through in-person encounters, text message, or social apps. She is sure to keep tabs on her close friends’ social media posts so she can comment on them and demonstrate their importance to her. For more distant connections, Rachel occasionally likes a picture, or messages a friend to see what’s up. The point is, building a network takes work. If Rachel doesn’t expend the relational work necessary to keep her network connections healthy, then she will ultimately lose them and her network of social support—a fearful prospect in the age of networked individualism.

The burden to craft a personal network and the possibility of losing one’s network community can ultimately mire young people in fear and anxiety. If you’ve seen a teenager panic when separated from his phone, then you’ve witnessed the struggle of being out of touch with friends. However, you’re also witnessing the fear of permanently losing network members by being temporarily out of touch.

The church is called to embody koinonia, an alternative operating system that delivers teenagers from the fear induced by networked individualism. The demand to create an egocentric network differs significantly from the communion of the church, in which youth are called, drawn and invited into the cloud of witnesses and the Body of Christ. In koinonia, belonging does not depend on personal effort.

Demand #2: Keep the Network Engaged

Building an egocentric network is not a one-time endeavor, rather it is necessary to keep the network alive by making oneself engaging, interesting and attractive, lest your network audience lose interest and slip away. Maintaining the interest and attention of the network as audience can be difficult, thus in a networked world, “impression management is key to developing a social identity.”[3] Getting likes is a competitive venture, and having just the right pictures, status updates, videos, tweets, and texts is paramount.

Like many teenage girls, Rachel is a master at curating her online image to maximize likes and minimize embarrassment. Rachel admits to agonizing over status updates, and fudging on her likes/dislikes when filling out profiles; she is keenly aware of what’s going to be interesting and sound cool to the members of her network. When her family visited Disney World last year, she was sure to post pictures and updates endlessly, hoping to attract likes, while keeping her network members engaged and interested in what she was doing. But when her youth pastor tagged her in an unflattering photo on Facebook, Rachel quickly removed the tag in hopes that her network members wouldn’t notice.

Rachel knows how to strike the right pose for group shots; she’s hyper aware of getting just the right knee bend, hand-to-hip placement, and tilt of the head in order to produce the best possible outcome. Reports show that the average woman takes seven selfies for every one that she posts, and Rachel is no exception.[4] In fact, seven seems a little low to her. “It totally depends on the day,” she says with a laugh. Social media are incredibly well-suited for the task of impression management, and while Rachel uses Instagram because that’s where her friends are, she’s also thankful for the built-in photo filters that allow her to tweak and edit her photos on the spot.

All of this is impression management at work, and it’s driven by the need to maintain the interest of one’s network members. But beneath all of the perfectly chosen words and poses, there are aspects to Rachel’s self that she keeps carefully hidden. The self that she presents online is shined and buffed, staged and produced to be consumed by her network members. Ultimately, there’s a difference between presenting the self and being the self, and the demand that teenagers engage their network audience leads them to hide the self rather than reveal the true self.

Communion, as an alternative social operating system, can release individuals to be themselves, as they find acceptance and love as sharers in Christ, and not based upon their own efforts.

Demand #3: Grow the Network Large

Having a few friends is not enough for the social system of networked individualism; rather “those with relatively big and diverse networks, including many weak-tie associates, gain special advantages” and are more likely to get the help, support or information they need.[5] Of course, maintaining close relationships with a large number of people is difficult. And that’s okay, because networked individualism doesn’t demand close relationships, it merely demands that you have connections with a variety of people. In fact many partial relationships are considered far better than a few tight ones in a networked world.[6] For example, having a large number of people who fill the relational role of “audience member” can collectively become an important resource when you need “the wisdom of crowds.”[7] Barry Wellman and Lee Rainie declare that, in a society of networked individualism, those with “broad-ranging networks are often in better social shape and have a greater capacity to solve problems than those who have smaller networks. Quantity does equal quality.”[8]

Social media are well-suited for helping teenagers like Rachel grow a vast network of partial relationships. With over 600 friends on her Facebook account alone, Rachel is unable to keep in touch with all of them, but she is able to drop birthday messages to important friends, and leave occasional likes on the posts of others in her network. Like others, when she needs the help or resource of a particular friend, that person is just a message away. Despite their longing to escape from partial and transitory relationships, the demand to grow the network pulls teenagers away from the presence and intimacy they desire. Instead, they find themselves in faceless relationships where they are not deeply known.

In contrast, the experience of koinonia leads us to declare one another to be brothers and sisters, as we engage in relationships of presence and knowing. Yet, instead of being a community of presence, church is often one of the most anonymous communities that teenagers encounter all week.

Demand #4: Be Socially Selective

Even though it’s necessary to maintain a large network of weak ties, networked individuals must be selective about the individuals on whom they spend their limited time and energy. “Tune your network by dropping people who don’t seem worth spending attention on regularly,” Internet guru Howard Rheingold advises his readers.[9] This kind of cutthroat social selection is necessary or else networked individuals might find themselves with a large social network filled with people incapable of actually giving them the support and help they need.

When nasty rumors began to fly around school about her close friend Michelle, Rachel was torn but ultimately decided it was best to keep her distance. “She’s kinda made her decision,” she told me, “I don’t want to get dragged into that.” While Rachel didn’t cut off all connection to Michelle, it wasn’t socially expedient for Rachel to spend much time on the relationship—and so she didn’t.

That’s how things work in the world of networked individualism, but in the communion of Christ the worthless and uninteresting are not unfriended. Rather, we’re called to clothe these members “with greater honor” (1 Corinthians 12:23). In the communion of Christ, teenagers are meant to receive love and belonging when they have no social value, and they in return are invited to give love without considering the social value of others.

Turning Our Attention to Communion

American adolescents are hungering for relationships characterized by presence and intimacy. Yet their search is increasingly pressured by the demands of networked individualism. Fulfilling these demands often puts teenagers at odds with their desire for meaningful relationships. Building, growing, and engaging a large network of partial connections leads youth toward anxious, weak, and instrumental relationships—something far less than the relationality for which they have been created, and for which they long. Networked individualism leaves youth hungry for relationships of presence, but there is a better way.

It’s time to turn our attention from the experience of teenagers and the social system of the culture around us, and fix our full attention on God’s intended social operating system for the church. As we’ve said previously, the way forward in youth ministry will not be discovered by focusing on technology, but rather by focusing on the proper nature of Christian koinonia. In an age of networked individualism, youth ministry cannot be content to offer better technology, but rather we must offer teenagers entry into a community that is powered by a completely different engine and logic. That’s precisely how the apostle Paul presents the idea of koinonia in First Corinthians, as a counter-cultural social system distinct from the surrounding world.

To understand how koinonia differs from networked individualism, it’s necessary to momentarily leave the 21st century and consider how Paul’s theology of koinonia contrasted what was happening in the 1st century. You might be surprised to find that our world and Paul’s are not so far apart.

*****

[1] Rainie and Wellman, Networked, 256.

[2] For an exploration of the potential benefits of networked individualism, see Rainie and Wellman’s book Networked.

[3] boyd, Why Youth Heart MySpace, 22.

[4] Sarah Coughlin, “This is How Much Time We Spend Taking Selfies Each Week,” Refinery29, April 24, 2015. Accessed at http://www.refinery29.com/2015/04/86241/women-selfies-average-statistics

[5] Rainie and Wellman, Networked, 263.

[6] Ibid., 41.

[7] Ibid., 264.

[8] Ibid., 266.

[9] Howard Rheingold, Net Smart: How to Thrive Online, 229.